A 20-year study published in February of 2026 has shown that one specific type of cognitive training can significantly reduce Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia diagnoses years later. This is the first time any study of any intervention or treatment has shown such a result—and it signifies a new era of brain health and Alzheimer’s prevention. The cognitive training that delivered this breakthrough result? An exercise that you can use in BrainHQ right now.

The original study

The original study—called the ACTIVE study—began in 1998. It was designed to test what types of cognitive intervention might improve cognitive function and real-world function, and how those effects might persist over time after training was complete.

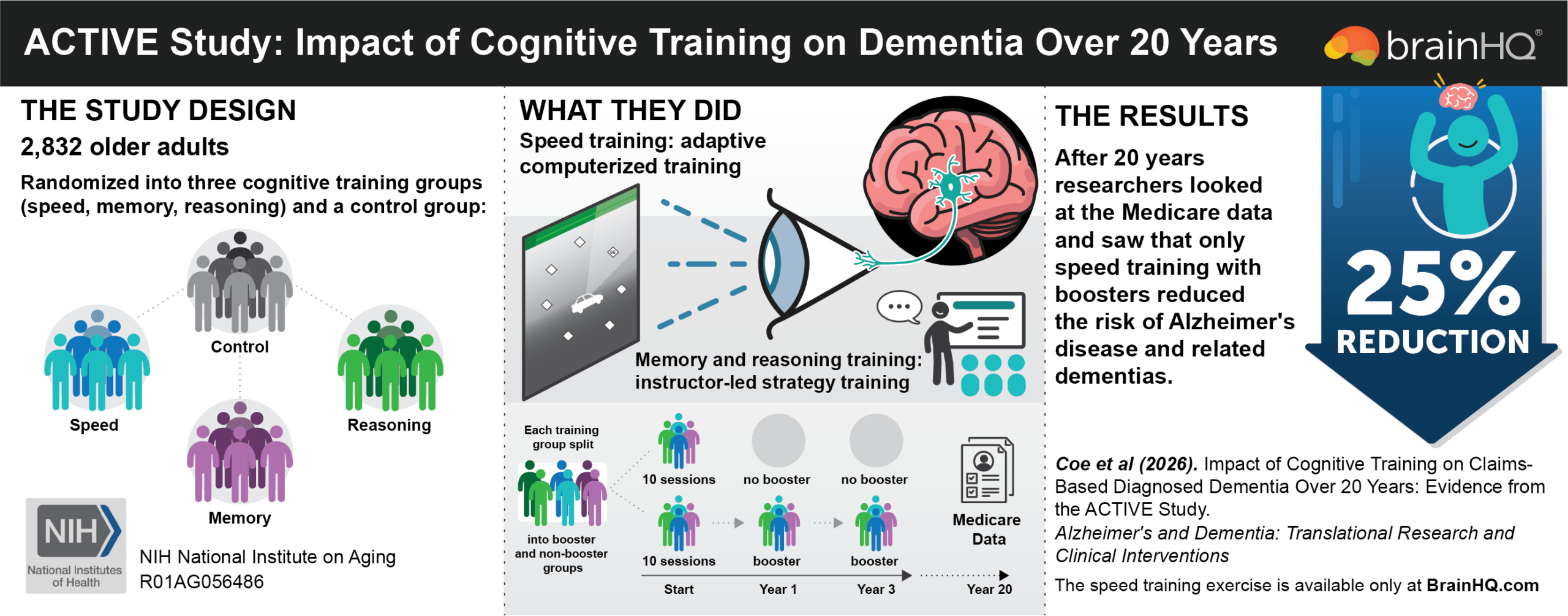

During this early period, researchers divided more than 2,800 people over the age of 65 into four groups: a memory training group, a reasoning training group, a speed training group, and a control group. The memory and reasoning training groups learned strategies to improve memory (like mnemonics) and reasoning (like pattern-recognition) in a class with an instructor.

The speed training group did something very different. They used a computerized brain training exercise designed to improve visual speed and attention. In the exercise, people had to focus their attention to determine whether an image in the middle of the screen was a car or a truck. At the same time, they had to divide their attention to notice where a specific image was located in their peripheral vision—all while the program got faster and faster to challenge their brain speed. If you’re a BrainHQ user, that might sound familiar, because the speed training exercise in ACTIVE became the Double Decision exercise in BrainHQ. While the study was still in progress, the science team from BrainHQ worked with the scientists from ACTIVE who invented speed training to make this incredible brain training technology broadly available on the BrainHQ platform.

Each of the training groups was asked to complete a training session twice a week for about an hour for the first five weeks of the study. At that point, some of the people in each group were done—but the others were asked to complete “booster” sessions. They did four more sessions about a year after their initial training, then again after about three years. In total, the people who did not do a booster session completed about 10 hours of training, and those who did the booster sessions did about 23 hours.

Researchers looked at the results of the ACTIVE study and found that in the short term, all of the training groups saw benefits. Each group improved at its target cognitive function, and all groups showed slower decline on everyday living skills. But on a host of other measures of real-world benefit, the most beneficial intervention was speed training. Safer driving, better mood, and more self-confidence were just a few of the many benefits for the speed training participants.

20 years later with new data

Twenty years after the original study, researchers tackled an ambitious project: to link up the data between every ACTIVE study participant and their Medicare data. This would allow researchers to evaluate the real-world effects of cognitive training on the kind of health data that only Medicare has—including whether a person had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia. No study of brain training has ever had access to this type of data.

What the researchers found was incredible: people who did the speed training and the boosters showed a 25% reduction in the risk of getting Alzheimer’s and dementia over the twenty year period. And the effect was specific—there was no benefit from either the memory or reasoning training (with or without boosters). Making the brain faster with speed training—and keeping it fast with annual booster training—is what worked.

Why this is a true breakthrough

This is the first randomized controlled trial of any intervention—drugs, exercise, nutrition, sleep, games—to show that a reduction in the risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia is possible.

Previous observational studies have shown an association between healthy living habits—like physical exercise—and reduced risk of dementia. In these studies, researchers observe a large number of people over time and see what happens—but they don’t ask anyone to change their actions in any way. As a result, researchers can’t be sure of what was the cause and what was the effect. There’s just no way to tell in this kind of study.

To sort out cause and effect, researchers have to do a randomized controlled trial where people are randomly assigned to specific treatments, and compared to a control group. That way, researchers can be certain that it’s the specific treatment that causes the effect. And that’s what makes the ACTIVE study results so strong: researchers know for sure that it’s the speed training and boosters that reduced the risk of Alzheimer’s and dementia.

“Years ago when I began building brain-plasticity-based training programs, I knew that this approach would eventually be shown to protect against Alzheimer’s and dementia.,” says Dr. Michael Merzenich, Emeritus Professor of UCSF and Chief Scientific Officer of Posit Science. “I’m delighted but not surprised to see these results.”

“To get such a strong result from such limited training is testimony of the power of brain-plasticity-based training,” he adds. “Just imagine if the participants in ACTIVE did more of this type of adaptive online training over time, targeting more brain functions. How much stronger would the benefits be?”

What it all means

These results mean that the age of dementia prevention has truly arrived. In the same way that we now understand that physical health conditions like Type 2 diabetes can be prevented with the right types of exercise and nutrition, we now understand that brain health conditions like Alzheimer’s and dementia can be prevented with the right kind of brain training. Previously, we might have thought that people should simply wait until their doctor diagnosed them with Alzheimer’s, and then take a drug that might slightly slow their decline. But now we know that people can take action—evidence-based, scientifically supported action—while they are still healthy to reduce their risk of dementia.

This is a new era for brain health—and the fact that you’re here, reading this news article, means that you’re part of it. Welcome to the future!

You can try Double Decision to see what it’s like—or access the full exercise with a subscription to BrainHQ.