Memory is a single word for a complicated brain process that actually takes many different forms. So what exactly is “memory,” and how can you keep your memory strong?

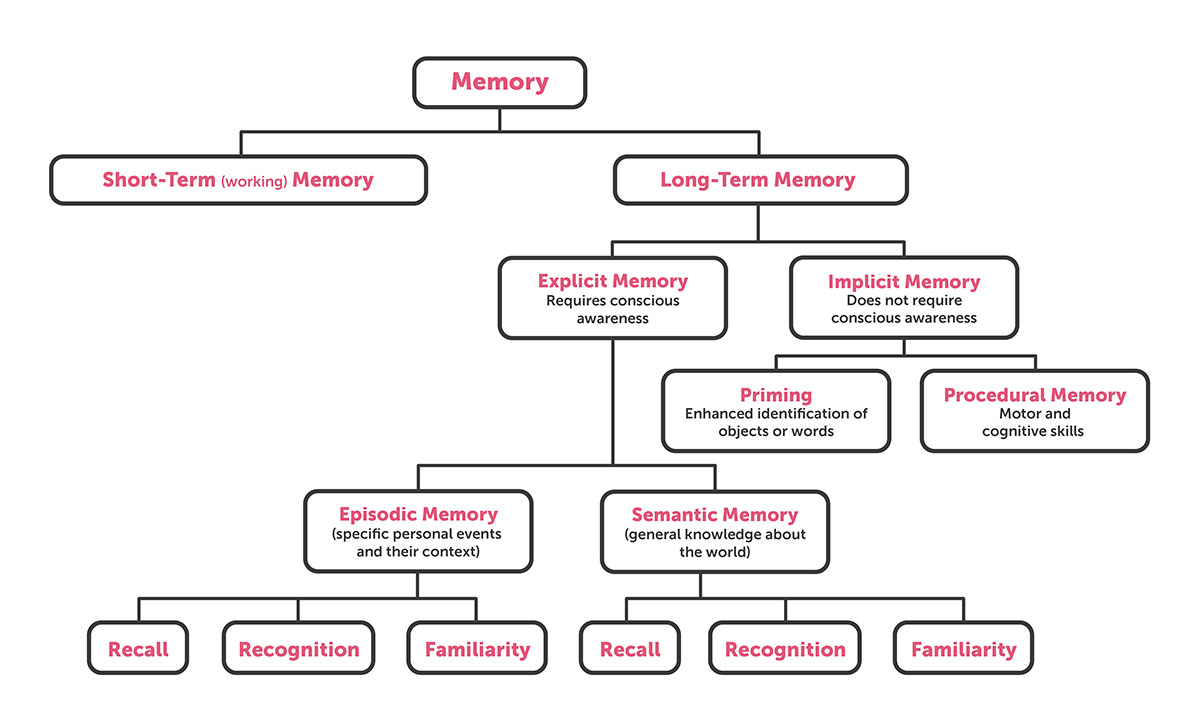

You’ve likely heard of the two biggest categories of memory: short-term (or “working”) memory and long-term memory. But within short- and long-term memory, there are subcategories.

Short-Term Memory

Short-term memory—closely related to “working” memory—is the short time that you keep something in mind before either dismissing it or transferring it to long-term memory. Short-term memory is shorter than you might think, lasting less than a minute. It’s what allows you to remember the first half of a sentence you hear or read long enough to make sense of the end of the sentence. But to store that sentence (or thought, fact, idea, word, impression, sight, or whatever else) for longer than a minute or so, it has to be transferred to long-term memory.

A newer concept for that brief type of memory is “working memory.” The two are often used interchangeably, but working memory emphasizes the brain’s manipulation of the information it receives (using it, storing it, and so on), while short-term memory is a more passive concept.

Long-Term Memory

A long-term memory is anything you remember that happened more than a few minutes ago. Long-term memories aren’t all of equal strength. Stronger memories let you recall something easily—for example, that Paris is in France. Weaker memories often come to mind only through prompting or reminding, like “it starts with a P.”

Long-term memory isn’t static, either. You do not imprint a memory and leave it untouched. Instead, you often revise the memory over time—perhaps by mixing it with another memory or incorporating what other people tell you about the memory. As a result, your memories are not always constant—and so are not always reliable.

There are many different forms of long-term memory. The two major subdivisions are explicit and implicit. Although understanding these differences is helpful, the divisions are fluid: different forms of memory often mix and mingle.

Long-Term → Explicit

Explicit memory (also called “declarative memory”) requires conscious thought—such as remembering who came to dinner last night or naming animals that live in the rainforest. Explicit memory is what most people have in mind when they think of “memory,” and whether theirs is good or bad.

Explicit memory is often associative; your brain links memories together. For example, when you think of a word or occasion, such as a wedding, your memory can bring up a whole host of associated memories—from white dresses to cakes to vows to dancing to a thousand other things.

Long-Term → Explicit → Episodic Memory

Episodic memory is one type of explicit memory. Episodic memory provides us with a record of our personal experiences. It is our episodic memory that lets us to remember the trip we took to Vegas, where we took our dogs for a walk yesterday, who told us that our friend Maria was pregnant. Any past event in which we played a part, and which we remember as an “episode” (a scene of events) is an episodic memory.

Long-Term → Explicit → Semantic Memory

Another type of explicit memory is semantic memory. It accounts for our “textbook learning” or general knowledge about the world. It’s what enables us to say, without knowing exactly when and where we learned, that a zebra is a striped animal, or that books have pages.

Long-Term → Implicit

Implicit memory (also called “nondeclarative” memory) is different from explicit memory in that it doesn’t require conscious thought. It allows you to do things by rote. This memory isn’t always easy to verbalize, since it flows effortlessly in our actions.

Long-Term → Implicit → Procedural Memory

Procedural memory is the type of implicit memory that lets us carry out tasks without consciously thinking about them. It’s our “how to” knowledge. Riding a bike, brushing our teeth, and washing dishes are all tasks that require procedural memory. Even what we think of as “natural” tasks, such as walking, require procedural memory.

Though it’s easy to do these tasks, it’s often hard to describe how we do them. Procedural memory likely uses a different part of the brain than episodic memory—with brain injuries, you can lose one ability without losing the other. That’s why a person who has experienced amnesia and forgets much about his or her personal life often retains procedural memory: how to use a fork or drive a car, for example.

Long-Term → Implicit → Priming

Implicit memory can also come about from priming. You are “primed” by your experiences; if you have heard something very recently, or many more times than another thing, you are primed to recall it more quickly. For instance, if you were asked to name an American city that starts with the letters “Ch,” you would most likely answer Chicago, unless you have a close personal connection to or recent experience with another “Ch” city (Charlotte, Cheyenne, Charleston…) because you’ve heard about Chicago more often.

In the brain, the neural pathways representing things we have experienced more often are stronger than those for things with which we have fewer experiences.

Both short-term memory and long-term memory can weaken with age or with cognitive conditions. For example, it can get harder to remember a password you just heard, remember the name of someone familiar to you, or complete a procedure that used to be easy. That makes it harder to get into your bank account, recall an acquaintance’s name, or remember every step in baking a cake you’ve baked a hundred times.

Enter BrainHQ

BrainHQ has been proven in hundreds of studies to improve attention and memory. Attention is important because when we pay attention—when we focus on something—we remember it better. A study published in October of 2025 showed that using BrainHQ actually increases the production of a brain chemical that is most closely associated with attention. Another study, the IMPACT study, showed that BrainHQ training can improve memory by the equivalent of 10 years. You can sign up to try BrainHQ for free at brainhq.com!